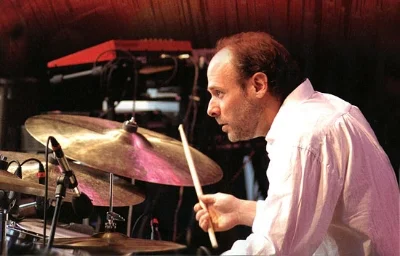

Jeff Ballard is one of the most accomplished sidemen in modern jazz. A ‘first-call’ drummer of his generation, the list of his performing and recording credits speaks for itself. He’s played with modern jazz greats Joshua Redman, Pat Metheny, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Guillermo Klein and Ben Allison. He’s anchored two of the great piano trios in recent memory, Chick Corea’s New Trio and, since 2004, the Brad Mehldau Trio. With Mehldau, Ballard shares rhythm-section duties with bassist Larry Grenadier. The two have known each other since they were teenagers, which might account for their uncanny connection. With Grenadier, and saxophonist Mark Turner, Ballard co-leads the trio Fly.

This week, we caught up with Ballard in Berlin, where he was playing the first gig on a tour with his latest project as a bandleader, Fairgrounds. Featuring virtuoso guitarist and vocalist from Benin, Lionel Loueke, pianist and vocalist Kevin Hays, and renowned bassist Reid Anderson – not on bass – but on electronics, the group stretched out on a set that seemed to float in all directions.

Following the performance, we asked Ballard what it’s like to be leading this group of extraordinary musicians:

It’s a collective feeling, and that’s the way I like to play music. My favourite bands I play with, of course there’s a leader, but we all play a huge role in making the band. It’s a collective. There’s an equality.

What’s different with Fairgrounds is that I’m insisting that there’s complete freedom in choice, musical direction, commentary. That’s the only criteria really. So, it’s fairly experimental. There isn’t a repertoire. We’ll build the book as the gigs go on. We’ll build and build and build from within ourselves.

I was just talking to some of the guys in the back. There’s that scary moment of stagnant waters, where nothing is going on, and you just sit there. The trick is to just bathe in that. Sit in that, and see if you can make it through without hurting anybody! See if you can come up with something vital.

Part of the unique approach comes from the fact that there is no bass player. Anderson, best known as bassist and composer in the co-lead trio, The Bad Plus, plays an electronic setup of his own invention with Fairgrounds. Ballard mentioned it took Anderson quite some time to design the instrument, and what comes out of that effort is a special ability to improvise while using electronics. In most settings, improvisation has to go on over top of pre-set electronic sounds, but Anderson has devised a means for interacting with the band. As Ballard put it,

It’s the nature of that instrument Reid’s playing. I asked him to play it. He just finished designing and developing that instrument, which took him half a dozen years to really come up with something where he can play it. That’s the big investigation, if he can improvise with the band with this new instrument.

In Fairgrounds’ music, the intentional lack of a centre is immediately noticeable. The band orbits around something unseen and unheard, interacting with near-complete freedom. The intelligence and sensitivity of each individual player is crucial to the group creating something coherent. Part of this, says Ballard, is the fact that each of these musicians – Loueke, Hays, Anderson, and certainly the drummer himself – has his own ‘little world.’ In other words, each individual voice has the ability to carry the band on its own. It’s in the unselfishness, the onstage interaction, that the music is made. Loueke is particularly impressive. Already emerging as a modern legend, the West African musician has spent years playing with Terence Blanchard and Herbie Hancock. He has three superb, must-listen releases from Blue Note Records: Karibu, Mwaliko, and the most recent, Heritage (co-produced with pianist Robert Glasper).

There is certainly the sense of deep friendship that comes through in Fairgrounds’ extended improvisations. These musicians have known each other for years, so their personalities – as well as their musical voices – interact, creating something joyous, while at the same time dissonant and challenging.

When we asked Ballard about his influences in leading the band, he had plenty to say. Beside such renowned leaders as Corea and Mehldau, Ballard toured for three years in the late 1980s with one of the greatest bandleaders of all – Ray Charles. ‘That was finishing school,’ said Ballard,

The big thing with Ray was the drama in telling a story with the music. There were times, we were playing the same songs – I was playing for three years – and he’d been playing these songs for thirty years. There were moments in ballads where I would look over and say, ‘Is he crying?’ I mean, he really lived it. The fact of drama, and how that translates into the music.

Ray had a foot stepping back into a real, old, soulful spot. I try to bring that into this context, where all of a sudden we’ll be swinging a real slow blues. There are some old school roots in there – just trying to tell a story. Build something that has tension and release – revelations. You know?

The approach Ballard takes as the leader of Fairgrounds allows for these revelations. Extended improvisations stretch out into elastic soundscapes, but a return to the story, the moments when tension is released and groove is laid down with impeccable precision, are the moments we listen for.

When asked what he admires about his band mate and long-time friend, Kevin Hays – who took lead on vocals during one tune – Ballard noticed, ‘I hear everyone he’s played with. He’s got an old soul. He’s played with all the old jazz cats, so he really went to school, you know? Up on the bandstand. He can play the blues like anybody. Very loose and also precise, clear.’ After listening to a set by Fairgrounds, it felt like we had all been a part of something: both the tradition of the music and the foreword thinking nature of what Ballard is trying to do – playing at once in total freedom, with the foundation of experience and the entire history of improvised music behind them. Is this what the future sounds like?